|

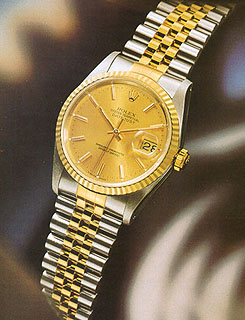

The Rolex Oyster Perpetual And it was never stylish. When other watches were thin, it was fat, when they were fancy, it was plain, when they converted to quartz, it remained steadfastly old-tech. In the nearly seven decades it has been around, it's been as fashion-resistant as it is water resistant. Somehow that hasn't mattered. The Rolex Oyster Perpetual is the most copied watch in the world. In its best known version, with fluted bezel, "Cyclops" magnifier over the date aperture and straight-line markers on the dial, it's the shining symbol of Switzerland's biggest luxury watch brand, its signature, as recognizable as a theme song. People around the world wear it as a status symbol and many who don't wear it aspire to. But popularity and prestige aren't the main reason the Oyster Perpetual, which debuted in 1933, is the century's most important watch. It's even more remarkable for its technical wizardry, which solved two problems that had stymied wristwatch makers for years. It had an impermeable case, which it inherited from its 1927 precursor, the Rolex Oyster (so named because it was sealed tight as an oyster). And it had the world's first truly effective self-winding device. (That's where the "perpetual" came from. The watch runs "perpetually" without needing to be wound as long as your wearing it.) The Oyster Perpetual was hence the father of every automatic watch on the market today. As Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf wrote, accurately if no too modestly in a brief memoire: These two inventions would give an extraordinary boost to the Swiss watch industry." It's ironic that two assets so highly prized by modern watch-wearers - water-resistance and self-winding - we're mere byproducts of their investors' struggles towards a different end. For what the designers really wanted wasn't a watch you could wear swimming - the very notion was preposterous at the time - or one that spared you the inconvenince of winding. What they wanted was a watch that would keep out dirt. Wilsdorf, the best-known champion of the wristwatch, had for decades been fighting a vigorous crusade to disarm critics of the still, in the '20's, relatively young invention. But the wristwatch had one problem Wilsdorf couldn't deny: because it was more exposed to the elements than pocket watches were, dirt was more likely to get into the case, and dirt is accuracy's natural enemy. So Rolex came up with the world's first truly impermeable case. It was constructed so that the pieces - case back, sides, bezel and movement ring, which held the movement in place - screwed tightly together. Gaskets made of lead also helped keep foreign matter out of the case. The winding stem screwed into a tube in the side of the case using a system of double-helical screws. (In the war against dirt, the winding-stem hole had posed a huge problem for watchmakers because it provided such an easy entryway.) An added virtue of the Oyster case: unlike several other supposedly impermeable cases, it did not rely on rubber, leather, or other materials that would deteriorate. The Oyster case was a triumph. It was so well sealed that, why, not even water could get in. Rolex proved it by suspending the watch in fish-bowl displays in jewelry stores and, more famously, by asking Mercedes Gleitze, the first British woman to swim the English Channel, to do so wearing a Rolex Oyster. Thus Rolex became, inadvertently, the inventor of the sports watch, generally defined nowadays as a watch that is water-resistant. By signing up Gleitze to wear the Oyster, then touting her record-breaking, Oyster-toting swim in an ad on the front page of London's Daily Mail, it also invented sports watch marketing. The Oyster case was a huge step forward but it still wasn't perfectly dirt-proof. If the wearer forgot to screw the crown down after winding the watch, dust entered through the winding stem hole. That's why Rolex developed a self-winding movement. That way, the crown would remain screwed down except for the rare times when the watch needed to be set. Others had tried to make an automatic wristwatch and failed. One of them was a Briton named John Harwook, who, in the 1920's, patented a movement whose mainspring was wound by a rotor swinging back and forth. The movement didn't work very well, though. It suffered damage from the impact of the rotor's slamming against the buffers that arrested its swing. Rolex improved on Harwood's device by removing the buffers. Instead, the rotor swung freely in either direction until gravity brought it to a stop. Rolex patented the device in 1932, and within a year the Oyster Perpetual was introduced. The watch has been evolving, slowly and subtly, since then. In 1945, Rolex introduced the Datejust model, with a date aperture at 3 o'clock. It remained the flagship Oyster Perpetual model until 1956, when Rolex added a day aperture at 12 o'clock, creating the Day-Date, also called the President, which became the brand's new star. Two years earlier, Rolex had added two distinctive features to the watch - the now-famous, ubiquitously imitated, fluted bezel and a tiny magnifying glass in the watch crystal above the date aperture, the so-called "Cyclops eye." Rolex has never looked back. |

It was never pretty. One watch industry old-timer remembers that people used to call it a "turnip," watch-business slang for a timepiece that's big and awkward.

It was never pretty. One watch industry old-timer remembers that people used to call it a "turnip," watch-business slang for a timepiece that's big and awkward.